The European Green Deal was unveiled by the VDL Commission only days after it took office. It is to be the central core of all policy work in the five years ahead and will put the EU firmly on the path to be the first climate-neutral region on the planet. In adopting this radical approach, the EU expects to encourage other regions to follow and to ensure that we collectively meet the goals set out in the Paris Climate Agreement of 2015.

The European Green Deal was unveiled by the VDL Commission only days after it took office. It is to be the central core of all policy work in the five years ahead and will put the EU firmly on the path to be the first climate-neutral region on the planet. In adopting this radical approach, the EU expects to encourage other regions to follow and to ensure that we collectively meet the goals set out in the Paris Climate Agreement of 2015.

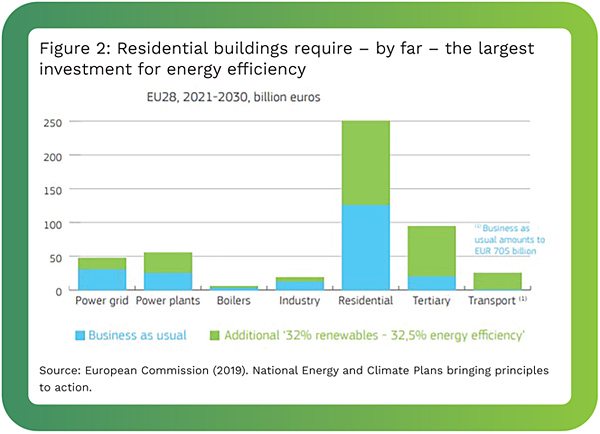

Given that across their lifetimes buildings are responsible for 50% of our energy use, 50% of our GHG emissions and 50% of all resources taken from the planet, it is evident that action to improve the energy performance of our buildings is an essential first step towards achieving the ambition of becoming climate-neutral by 2050. The big, fresh idea contained in the European Green Deal is a commitment to launch a Renovation Wave across the EU that will be designed to reap the full potential tied up in our building stock. It suggests three segments to start the wave rolling: schools, hospitals and social housing.

This level of ambition is welcome and it's very encouraging to campaigners like me that the VDL Commission has pinned its colours to the same flag post on which we have been flying our colours since 2011. One of the major questions to be asked in relation to the European Green Deal is how will it be paid for?

I do not intend to exhaustively go into all the available sources for financing – of which there are many. No, in this article, I just wish to expose one large, under-used, reservoir of financing that is available to the Member States and that I believe should be fully used to finance the energy renovation of the building stock in the EU: carbon revenues.

Maximising the impact of carbon revenues through energy efficiency

Many of the financing mechanisms that are available to implement the European Green Deal are adaptations of traditional approaches. While the EU Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS) has been in place since 2005, with prices expected to rise in the future, it will represent a new, substantial source of funds. The World Wildlife Fund (WWF) Maximiser project estimates that by 2030, the ETS could deliver revenues of €200bn to the Member States of the EU.

Pricing carbon aims to stimulate action to reduce emissions in two ways. First, through price signals that prompt a 'demand response'; by increasing the overall price consumers pay for carbon-intensive energy, the argument is that they will have incentive to use less (or be more conscientious about energy use). In the power sector - so far, the most important sector covered by the ETS - the second, more systemic incentive of carbon pricing is to drive change in the dispatch order of power generation, such that the extra cost to fossil-fuel plants makes their bids higher and lower-priced cleaner power generation will be selected earlier in the supply mix. Depending on the carbon price and the types of power plants in a power market, this impact on dispatch - the so-called 'merit order effect' - can have either moderate or negligible impacts on emissions. Unless lower-emitting resources are actually available to be run more often and carbon prices are high enough to prompt their use, the actual impact on dispatch is often rather low.

The introduction of new carbon taxes and carbon prices is challenging and struggles to gain public support in many areas, as the cost of the schemes are passed on to consumers through the cost of energy. With the carbon price in the EU ETS currently low - at just over €20 - the reality is that each tonne of carbon saved carries a cost of €248 for consumers. It is well known that power markets magnify the consumer cost of carbon prices. At €20/t, however, carbon prices are not effective on either front. How much consumers reduce use in response to the price signal is very low and no substantial shift has been noted in dispatch order.

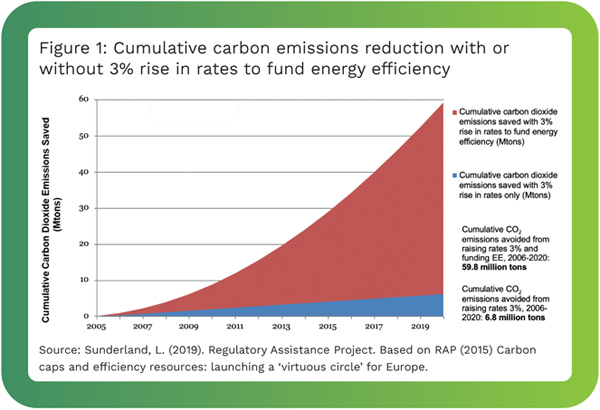

Given that passing the costs associated with CO2 emissions on to both producers and consumers is a core element of carbon pricing, it effectively raises the value of units of carbon-intensive/fossil-based energy that don't need to be produced or consumed. In this regard, using carbon revenues to support investment in energy efficiency renovations is a straightforward way to buffer the costs. In fact, a recent study by the Regulatory Assistance Project, based on evidence both from Europe and abroad, shows that directing carbon revenues to energy efficiency saves 7-9 times more carbon than price mechanisms alone, while also delivering other benefits. (Figure 1).

Additionally, investment in improving the energy performance of buildings can offset current regressive forms of revenue generation - i.e. taxes on energy bills - that have higher impacts on low-income households. Taxes calculated as a percentage of income and expenditures clearly place a much heavier burden on such households.

At least three Member States have programmes that link carbon pricing to energy efficiency. Germany dedicates KfW loans to such projects while in France, the Association national de l'habitat (ANAH) targets renovations of low-income households.

One stand-out example, which could be replicated within the roll-out of the European Green Deal, comes from the Czech Republic, where a 2012 law requires that at least 50% of carbon revenues be devoted to measures that reduce GHG emissions. The Czech scheme directs half of the recycled revenues toward the New Green Savings Scheme, a building renovation programme recognised to be among the most cost-effective energy saving schemes across all sectors in the country.

Over the period 2014-18, €350m was distributed for the energy renovation of over 32,000 dwellings. These subsidies offered to households to undertake renovations achieve a leverage factor of about 1:3, with each euro invested by the State attracting a further three euro of private (householder) investment. If this 1:3 return was to be sustained and 100% of national revenues were to be recycled into the scheme, by 2030 in the Czech Republic alone, ETS revenues of €4-7bn could deliver €12-21bn of investment in renovation.

An evaluation of the broader benefits of these investments found that for each €1m of State investment, a return to public budgets of €0.97 to 1.21m accrued through income tax paid by companies and their employees, lower costs to social and health insurance, and reduced payout of unemployment benefits. In parallel, the expenditure induced GDP growth of between €2.13 and 3.39m.

Ultimately, the evaluation shows that all of these benefits to public budgets and the economy were achieved while reducing CO2 emissions far beyond what could have been done by using the same money to abate CO2 in power markets.

If similar programmes were rolled out across the EU as part of the Renovation Wave, the impacts would be exponential.

Louise Sunderland from the Regulatory Assistance Project at Renovate Europe Day 2019 presenting the research on recycling of carbon revenues for energy efficiency. Photo: ©Simon Pugh Photography

Conclusion

The ambition of the European Green Deal may have taken some by surprise and they may believe that the ambition cannot be achieved because adequate financial resources cannot be found to meet the ambition. As can be seen from this article, there are innovative ways to finance elements of the Green Deal - such as the Renovation Wave - that will simultaneously help the Green Deal to succeed and spread benefits to society at large.

When the Member States come to roll out their Renovation Waves, I hope that they will use their carbon revenues to finance them!

Contact information:

Rond Point Schuman 6, 8th Floor,

1040 Brussels, Belgium

Tel: +32 2 639 1011

Email: adrian.joyce@euroace.org

MaxiMiseR ETS full technical report